Ai Weiwei at The Royal Academy: “The Art always wins”

This autumn sees the major works of controversial artist Ai Weiwei, on display for the first time at London’s Royal Academy. Naturally, The Practice team couldn’t wait to make a visit.

Spanning Ai Weiwei’s return to China from the US in 1993 up to the present day, this incredible exhibition features his most celebrated and fascinating masterpieces. We were amazed by the stories behind each one of his works, all of which highlight aspects of his life, homeland, and fraught relationship with the state.

The first piece displayed was the dramatic Bed, a sprawling piece of dark reclaimed ironwood that catches the eye with its endless ridges and smooth curvature. Bed is actually a map of China, which is apparent from a horizontal viewpoint- the curves map out the country’s border. Wei’s fascination with China’s topography is evident throughout the exhibition- Bed forces the reader to consider unfolding geographical borders. Another of his works, a large structure of interlocking wooden furniture, also represents a map of China, but the viewer is allowed to experience this in a different way. Comprising conjoined pieces of wooden furniture, this composition fills the whole show space, enabling the viewer to wander between the interweaving pieces that depict China and Taiwan. Uniquely, we are told that from a birds-eye perspective, the country’s shape and borders are also evident.

Bed

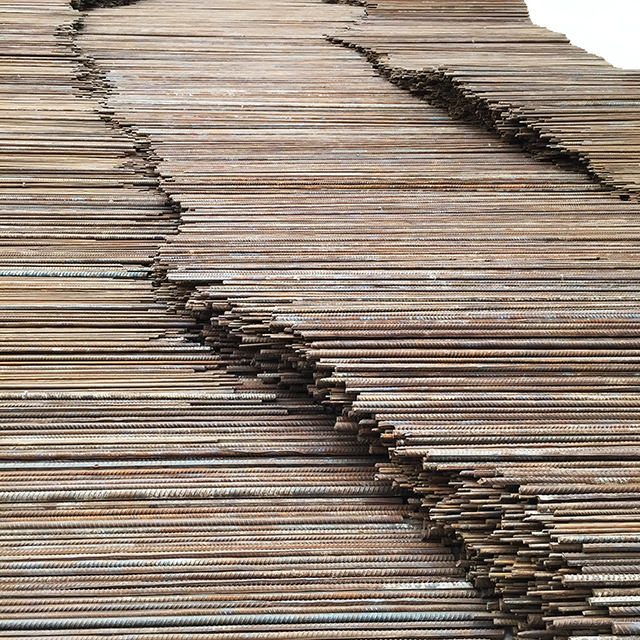

One of our favourite works was the evocative Straight, a piece created to commemorate the Szechuan Earthquake disaster of 2008. Crafted from over 100 tonnes of metal collected from destroyed Chinese schools, it is a surprisingly life-like representation of a powerful wave.

Straight

In the next room, we were presented with He Xie, an eye-catching piece featuring 3200 crabs, handcrafted from porcelain. We learn that the Chinese word for “crab” is “hie xie”- when spoken, this sounds the same as the Chinese word for “harmonious”- “he xie”. Looking at the tangled pile of crabs which comprise this piece, the result is discordance and chaos- anything other than its namesake.

He Xie

Ai Weiwei has openly demonstrated his love for social media, using the online space to vocalize his antagonistic relations with the Chinese government. In 2005, Ai started blogging on the social network, Sina Weibo, China’s Twitter equivalent. He posted to the site for over four years, with content featuring harsh social commentary, critiques on governmental policy, autobiographical accounts, and musings on art and architecture. However, his blog was finally shut down by the site due to a number of controversial posts surrounding the Beijing Olympics and the Sichuan Earthquake. Following this, he then turned to Twitter, where up until 2013, he spent around 8 hours online each day. Due to his outspokenness and the political nature of his online activity, he has been investigated and arrested on numerous occasions, placed under house arrest, and even served jail time.

His time under house arrest is portrayed in an enormous construction featuring six large “boxes” with front doors, and behind each, figurines of Ai surrounded by police, as he is watched in his own home while eating, sleeping, and even using the bathroom. The viewer is allowed several unique vantage points from which to survey the scenes- these are through a small opening in the rooftop, and through isolated windows in each of the houses.

We also see his take on authoritarianism brought to life in the piece, Cao or Grass. In this, the viewer is presented with a large marble rectangular carving comprised of conjoining hexagonal titles. These support hundreds of blades of grass pointing upwards- this, we are told, signifies a generation’s defiance against the Chinese state. This piece also features two surveillance cameras on opposite sides of the room, reminding us that the watchful eyes of the police are never far away.

Cao

We left feeling in awe of these incredible pieces, and with a huge admiration for Ai Weiwei’s creativity and craftsmanship. His work demonstrated a reverence for the past, with antique and cultural artefacts given a playful contemporary spin. And of course, we were confronted with Ai’s artistic acts of rebellion, revealing a truly audacious spirit behind each piece. The government, as Ai Weiwei noted, may have been able to crush his freedom, watch his every move, and even destroy his studio, but in the end, “The Art always wins”.

Have you visited Ai Weiwei’s exhibition yet? We can’t recommend it enough! We’d love to hear your thoughts if you have, so please tweet to us @PracticeDigital and share your comments on our Facebook page.

Featured image: “Golden Age” by Ai Weiwei